American Indians

A story told for thousands of years.

More than 14,000 years ago, peoples arrived to what we now call the Americas. Over thousands of years, diverse American Indians built empires on this land, constructing sophisticated cities, and developing elaborate trade networks and complex social systems.

But in the 16th Century, when Europeans arrived on the shores that would become the Texas Gulf Coast, these longstanding American Indian civilizations were disrupted. Control over resources, including food and land, was taken from them, displacing and devastating many powerful American Indian tribes–and destroying many others.

We must be wary... Naguatex Caddi

Coastal Inhabitants

What is now known as the Texas Gulf Coast was home to many American Indian tribes including the Atakapa, Karankawa, Mariame, and Akokisa.

They were semi-nomadic, living on the shore for part of the year and moving up to 30 or 40 miles inland seasonally. They adapted well to life on the coast, fishing, hunting, and gathering roots and other plant foods. They invented resourceful ways to solve everyday challenges, including fending off mosquitos by covering their bodies in shark and alligator grease.

Karankawas

Karankawas were the first people Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca met when he washed up on the Texas shore near Galveston Island in 1528. Their meeting was the first documented encounter between American Indians and Europeans in present day Texas. While the Karankawa fed and sheltered Cabeza de Vaca and his companions, the tribe responded very differently to the French and Spanish colonizers who arrived later. Karankawas initially greeted René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and the members of his expedition when they arrived in Matagorda Bay in 1685. However, after La Salle's men stole a canoe from the Karankawa, relations soured and the two groups fought against each other frequently. After several hostile acts on both sides, Karankawas attacked La Salle’s settlement, Fort St. Louis, in 1688, leaving no survivors except for the children, who were adopted into the tribe.

When the Spanish began establishing a presence in Karankawa territory in the 1700s Karankawas resisted the Spaniards’ efforts to convert them to Christianity and confine them to missions. When Franciscan priests built Mission Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga at Matagorda Bay, the nearby Karankawas refused to relocate there or accept the priests’ teachings. Within just four years, the Spanish relocated the mission elsewhere to serve other tribes.

While Karankawas withstood initial contact with the Spanish, their fortunes changed in the early 1800s. Comanche attacks, disease, and conflicts with European-Americans all took a heavy toll on the tribe and their numbers began to decline sharply. In 1858, the few remaining Karankawas were living near Rio Grande City when a group of men led by Juan Nepomuceno Cortina attacked and killed them all, decimating the tribe.

Farmers and Traders

While some American Indians, such as Karankawas, moved seasonally to fish, follow wild game, and gather plants for food, others stayed in one place and built large cities and farms.

Caddos living in East Texas and Jumanos living in West Texas were both farmers and traders who developed wide-ranging trade networks and relationships with other American Indian tribal groups and Europeans.

Caddos

Since their arrival in present day Texas more than 1,200 years ago, Caddos built large village complexes, created elaborately designed ceramics, and traded in networks that spanned thousands of miles. Caddos lived in settlements of several hundred people. They lived in a matriarchal society, meaning they traced their descent and inherited leadership positions through the female line. They built earthen mounds at the center of their villages for their religious ceremonies and burials of social elites. They farmed corn and other crops, and hunted deer, rabbits, and bison.

Around 1500, Caddos developed a complex political system made up of alliances between different bands and tribes, and reached a peak population. Located between the Great Plains, Eastern Woodlands, and present-day Arizona and New Mexico, Caddos were in an ideal location to trade with tribes all over the continent. They maintained vast trading networks, exporting salt, pottery, and bois d’arc wood for making bows, and importing seashells, copper, and flint.

When French and Spanish merchants arrived in Texas and the surrounding area, Caddos began trading with them as well. This contact brought new diseases that had a devastating impact. Between 1646 and 1816, the Caddo population dropped by 95%. In 1859, the United States government forced 1,050 Texas Caddos to relocate to a reservation in present-day Oklahoma, removing them from the homeland they had occupied for more than 1,000 years.

Jumanos

Deep in present-day West Texas, Jumanos developed their own complex political alliances, trading networks, and farming practices. They lived along rivers and near springs, where they raised corn, squash, and beans. They traded with other tribes for things like pottery, animal hides, salt, and piñon nuts. Jumanos developed good relationships with Europeans, serving as guides to Spanish explorers and sometimes even acting as middlemen between other tribes and the Spanish government. In the early 1700s, Apaches began moving into Jumano territory. Unable to fend off the invaders, Jumanos eventually joined the Apaches. Within 100 years, the Jumano no longer existed as a separate tribe.

People of the Plains

Comanches and Apaches ruled large regions of present-day north and west Texas on horseback, hunting bison and raiding villages with remarkable effectiveness.

Pushed out of their homelands on the Great Plains, these tribes arrived in Texas looking for new territory. They found a land already occupied by Jumanos, Coahuiltecans, Cocoimes, Chisos, Tobosos, Tawakonis, Wacos, Kiowas, and other tribes, creating conflict over who would control the land.

Comanches

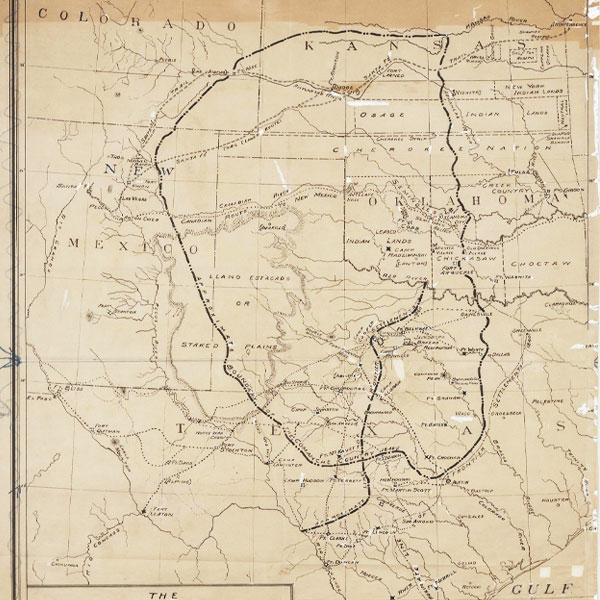

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, multiple, independent bands of Comanches migrated south from present-day eastern Colorado and western Kansas. They waged war on the other tribes in their path, including the Apache. Within a century, they controlled a vast territory called the Comanchería. Comanches roamed this territory where they hunted bison and deer, traded with their neighbors, and raided their enemies’ settlements.

While Comanches displaced Apaches and other tribes when they moved into the region, they soon found themselves threatened with the same fate. Comanches were able to make relative peace with the Spanish and Mexican governments. However, after Texas won its independence in 1836, Texas leadership began a process of extermination. Increasing numbers of Anglo Americans poured into the Republic of Texas, creating conflict with the Comanches, who had controlled the land and its resources for nearly 150 years.

The conflict escalated when Texas joined the United States and more Anglo settlers moved in, squeezing Comanches into a smaller and smaller territory. The systematic slaughter of the bison herds by new Anglo settlers, stressed Comanches even further. By the 1870s, Comanches had been weakened by disease and decades of war. Unable to fight any longer, Chief Quanah Parker surrendered and led his people to a reservation in present-day Oklahoma in 1875.

American Indians in Texas Today

American Indians from diverse tribal nations continue to live and work in Texas today. Regardless of their tribal affiliations, many keep their ancestors’ memories, traditions, cultures, and languages alive.

Only three federally recognized tribes still have reservations in Texas, the Alabama-Coushatta, Tigua, and Kickapoo. The state recognized Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas has its headquarters in McAllen. The Caddo, Comanche, and Tonkawa are officially headquartered in Oklahoma.

Banner image Comanche Feats of Horsemanship, 1834–1835, by George Catlin. Image courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.487

American Indians Timeline

Peoples settled in what is now Texas thousands of years before European explorers arrived in North America. Some American Indian oral histories recount how their ancestors traveled to the area by water or land. A large amount of stone artifacts made at least 16,000 years ago have been found in Central Texas. For many years, scientists believed that the first Americans came from Asia 13,000 years ago. The discovery of these artifacts suggests that humans came to the Americas much earlier.

Pre-Cloves Projectile Point. Courtesy Gault School of Archaeological Research, San Marcos, Texas

Peoples who lived in the area at the end of the Ice Age are referred to as the “Clovis” people by archaeologists. These people shared the land with mammoths, mastodons, and other Ice Age animals. They traveled long distances to hunt these animals with spears. They also used projectile points and other tools made of Alibates flint. Their stone tools have been found more than 300 miles from the stone's source.

Alibates. Courtesy Texas Beyond History, a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

The “Folsom” people lived a hunter-gather lifestyle very similar to the Clovis people. With the mammoth and many other big game species from the Ice Age extinct, the Folsom people followed large herds of bison that were larger than the bison of today. They hunted with a weapon called the atlatl and dart. This weapon system consisted of two parts: a "throwing stick" and a dart which looks similar to an arrow but was much longer.

Prehistoric hunters used atlatls to hurl these darts at their prey. Courtesy Texas Beyond History, a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

The “Archaic” people that called the present-day Texas Panhandle home lived in an environment that was rich in various plants and animals. They were slowly transitioning from being nomadic hunter-gatherers to farmers. They gathered various types of plant materials: seeds, roots, berries, and anything else that was edible. They would grind the seed into meal using tools called a “mano and matate” made out of sandstone or dolomite.

Striations, stains, and polish cover this limestone tool that may have been used for a variety of purposes, including grinding. Courtesy Texas Beyond History, a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

More than 5000 years ago in present-day Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, people began to grow corn, beans, and squash. The switch from a nomadic hunter-gatherer life style to horticulture contributed to more reliable food sources and settled lifestyles. Populations grew and cultures flourished.

Varieties of maize found near Cuscu and Machu Pichu at Salineras de Maras on the Inca Sacred Valley in Peru, June 2007. Courtesy Smithsonian Institute, photographer credit Fabio de Oliveira Freitas

"Rock art" including pictographs (painted images) and petroglyphs (carved, or incised images) was made by people at least 4,500 years ago throughout the Lower Pecos region of present-day Texas. The symbols in the “White Shaman” mural depict a creation story that can still be interpreted today by Huichol Indians in Mexico.

Panther Cave Rock Art. Courtesy Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center. Site jointly owned by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the National Park Service

Beginning at least 2,000 years ago in a Hueco Mountains’ canyon near El Paso, ancient Puebloans held ceremonies where they placed offerings in a cave. The Pueblo people believed that caves were portals to a watery underworld. Among the artifacts found in Ceremonial Cave were a finely crafted bracelet and pendants made of shells from coastal areas hundreds of miles away. These artifacts are evidence of the vast trade routes that existed between diverse communities.

Turquoise armband, 700–1450 CE. Courtesy Texas Archeological Research Lab, The University of Texas at Austin

The bow and arrow replaced the atlatl around 700 C.E. The new technology spread across much of North America around this time. Its precise origin is unknown, but it may have been brought into the region by new migrants. The bow was lighter and required fewer resources to make. The arrow was much more lethal than a spear because of its speed, silence, and accuracy.

Scallorn Points. Courtesy Texas Beyond History, a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

It is said that Texas owes its name to the Caddo. "Tejas" is a Spanish spelling of the Caddo word that means "those who are friends." Archaeological evidence in the form of fine ceramic pottery indicates that Caddo communities existed in the area as early as 800 C.E. The agriculture-based Caddoes lived in villages and large fortified towns surrounding large plazas with earthen mounds. Atop of the mounds were temples, council houses, and the houses of the tribe’s elites.

Large settlements with mound centers like this existed up and down the Mississippi River and were interconnected through trade. The largest of these fortified communities was Cahokia, located near present-day St Louis, MO. One of Texas's best examples of a Caddo mound is located in present-day Cherokee County.

Caddo Pot made by Jeri Redcorn, Caddo

The “Antelope Creek” people lived in the present-day Texas panhandle between 1150 and 1450. They lived in pueblo like villages where they practiced horticulture and bison hunting. Over a period of 300 years, they dug hundreds of quarries for better flint to make stone tools. Pottery fragments found at Antelope Creek sites provide evidence of extensive trade. The Antelope Creek people left the area abruptly around 1450 AD, perhaps because of drought conditions, disease, or the arrival of hostile Apaches to the area.

Antelope Creek Pottery Sherds. Courtesy Texas Beyond History, a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

Historians believe that the Apache moved down from their native territory in Canada and into North America sometime between 1000 and 1400. They belong to the southern branch of the Athabascan group, whose languages constitute a large family, with speakers in Alaska, western Canada, and the American Southwest.

By the 1600s two groups settled in Texas — the Lipan Apache and the Mescalero. The Mescalero eventually moved on to present-day New Mexico. The arrival of the Apache would begin to alter the trade and territorial claims among the diverse tribes who had settled the area before them.

Lipanes, From the Manuscript Collection: Jean Louis Berlandier, 1827 - 1830. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK

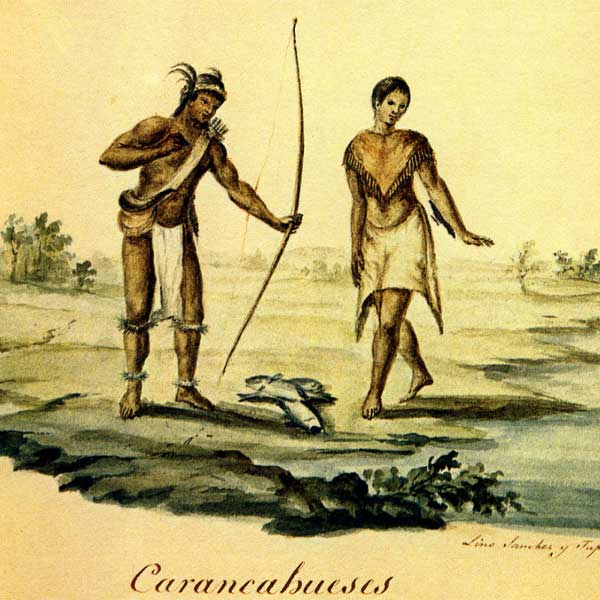

The Karankawa first encountered Europeans when Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca washed up on a Galveston beach in 1528. This encounter, which Cabeza de Vaca wrote about in his diary, is the first recorded meeting of Europeans and Texas American Indians. The Karankawa were several bands of coastal people with a shared language and culture who inhabited the Gulf Coast of Texas from Galveston Bay southwestward to Corpus Christi Bay.

Karankawa, From the Manuscript Collection: Jean Louis Berlandier, 1827 - 1830. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK

Almost 50 years after their first encounter, the Jumano were revisited by the Spanish in 1629. This would mark the beginning of their relations with the Spanish. The Jumano lands stretched from northern Mexico to eastern New Mexico to West Texas. Some Jumano lived nomadic lifestyles, while others lived in more permanent houses built of reeds or sticks or of masonry, like the pueblos of New Mexico. The Jumano were renowned for their trading and language skills. In time, these expert traders helped establish trade routes as well as diplomatic relationships among American Indians, the Spanish, and the French.

Jumano, Drawing by Frank Weir. Courtesy Texas Beyond History, a public education service of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

Led by the religious leader Po’pay from the Pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh, Pueblo people revolted against the Spanish colonists and drove them out of present-day New Mexico. After the revolt, Pueblo people began trading the horses they had taken control of. The acquisition of horses, and the ability to travel longer distances more easily, would transform the territorial politics between tribes throughout America.

"Po'pay" by Artist Cliff Fragua, 2005. Courtesy Architect of the Capitol

The Mayeye, a Tonkawa Tribe, first encountered La Salle and his French colonists in 1687. The Tonkawa belonged to the Tonkawan linguistic family that was once composed of a number of small sub-tribes that lived in present-day Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. The word "tonkawa" is a Waco term meaning "they all stay together." In the years to come the Tonkawa would have changing relationships with the Spanish and the French.

Tancahues, From the Manuscript Collection: Jean Louis Berlandier, 1827 - 1830. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK

Circa 1700

In 1706 Spanish officials in New Mexico documented the presence of numerous Comanches on the northeastern frontier of that province. As the Comanches moved south, they came into conflict with tribes already living on the South Plains, particularly the Apaches, who had dominated the region before the arrival of the Comanches. The Apaches were forced south by the Comanche and the two became mortal enemies.

Plains Indian Girl with Melon, 1851–1857. By Friedrich Richard Petri. Courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

The first reference to the Comanche in present-day Texas comes in 1743, when a small scouting band appeared in San Antonio looking for their enemies, the Lipan Apache. The Comanches were to become the most dominant people in the area. The name "Comanche" comes from an Ute word that means "enemy." They refer to themselves as the "Nʉmʉnʉʉ" or the "people." The Comanche were originally a Great Plains hunter-gatherer group, but after acquiring horses, they expanded their territory. They became horse experts and migrated into Texas in order to hunt bison and capture the wild horses that roamed the land. They eventually claimed vast areas of north, central, and west Texas as part of "Comancheria."

Comanche Feats of Horsemanship, 1834–1835, by George Catlin. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.487

Ever since the Spanish arrived in the San Antonio area, the Lipan Apache have been at war with them. When the enemy Comanche arrived to the area, the Apache agreed to a peace treaty with the Spanish. The two buried a hatchet in the ground in a ceremony in San Antonio. This led the Spanish to move forward with plans to build missions in Apache territory.

Spontoon Tomahawk. Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, Canyon, Texas

Originally from the area of present-day Kansas, a band of Wichitas moved from Oklahoma and settled along the Red River near present-day Nocona, Texas. They would live there until about 1810, when they gradually returned to present-day Oklahoma. The Wichita called themselves Kitikiti'sh, meaning "raccoon eyes," because the designs of tattoos around the men's eyes resembled the eyes of the raccoon. They lived in villages of dome-shaped grass houses. They farmed extensive fields of corn, tobacco, and melons along the streams where they made their homes and seasonally left their villages for annual hunts.

Wichita paint bag, 1800s. Courtesy The Field Museum, Cat. No. 59357

In response to the destruction of Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá, forces of 600 Spanish soldiers attacked the Taovaya (Wichita) village on the Red River. With horses and French weapons, the Wichita were a stronger force than the Spanish. The Spanish were defeated and forced to retreat.

French musket, 1700s. Courtesy Red McCombs Collection, Georgetown

The Spanish negotiated a treaty with the Comanche, who agreed not to make war on missionized Apaches. Continued conflicts with Apaches made it impossible for Comanches to keep their promise. This ultimately led Spanish officials to advocate for breaking their alliance with the Apache in favor of a Spanish-Comanche alliance aimed at subduing the Apaches.

Comanches, From the Manuscript Collection: Jean Louis Berlandier, 1827 - 1830. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK

As a result of British colonial expansion from the east, the Alabama and Coushatta Tribes began to migrate from what is now Alabama to the area of Big Thicket in present-day Texas. By 1780 they had moved across the Sabine River into Spanish Texas.

Cutchates, From the Manuscript Collection: Jean Louis Berlandier, 1827 - 1830. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK

With the help of the French Governor of Natchitoches, Spain made treaties with Caddo, Wichita, and Tonkawa tribes. One year later, also with the help of a Frenchman, Spain made a treaty at San Antonio with a Comanche band. Other bands, however, continued to raid Spanish settlements.

Comanche War Bonnet, 1946–1970. Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, Canyon

Since they first arrived to the Americas in the early 1500s, European diseases decimated diverse indigenous communities. In 1775 a smallpox epidemic killed hundreds of thousands of Europeans and Native peoples in North America. The virus was carried by people along the trade routes from Mexico City and moved north to Comancheria and farther north to the Shoshone. An estimated 90% of the American Indian population died from epidemics. The deadly diseases greatly shifted the balance of power between American Indians and Europeans.

Detail of Cabello to Croix, reporting smallpox epidemic, 1780. Courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

El Mocho, a Lipan Apache who as a child was captured and adopted by the Tonkawa, became a chief of the Tonkawa after a small pox epidemic killed most of the tribe’s elders. Hoping to free his people from Spanish control, he formed a loose confederacy of groups that included the Tonkawas, the Lipan Apaches, and some Comanches and Caddos.

Hand-colored stone lithograph of a West Lipan Apache warrior sitting astride a horse and carrying a rifle; from Emory's United States and Mexican Boundary Survey, Washington, 1857. Courtesy Star of the Republic Museum

The Comanche accepted a peace deal with the Spanish, allowing Spaniards to travel through their lands. In exchange, Spain offered to help the Comanche in their war with the Apache. Peace between the Spanish and Comanche lasted 30 years. The Comanches were to become the dominate force in the area, both in trade and warfare.

Cabello to Rengel, reporting on visit made to Béxar by Comanche captain to confirm peace treaty, 1785. Courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Cherokees were first reported in Texas in 1807, when a small band established a village on the Red River. American expansion had forced them to the west. They were an agricultural people whose ancestral lands covered much of the southern Appalachian highlands, an area that included parts of Virginia, Tennessee, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama.

In the summer of that year, a delegation of Cherokees, Pascagoulas, Chickasaws, and Shawnees sought permission from Spanish officials in Nacogdoches to settle members of their tribes in that province. The request was approved by Spanish authorities, who intended to use the displaced tribes as a buffer against American expansion.

"Cunne Shote, Cherokee Chief," by Francis Parsons, 1751-1775. Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation, 1955. Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa OK

In 1822 Cherokee Chief Bowl sent diplomatic chief Richard Fields to Mexico to negotiate with the Mexican government for a grant to land occupied by Cherokees in East Texas. After two years of waiting to receive a grant, Richard Fields tried to unite diverse tribes in Texas into an alliance and began to encourage other displaced tribes to settle in Texas.

Chief Bowl, Courtesy Jenkins Company. Courtesy Prints and Photographs Collection, Texas State Library and Archives Commission. #1/102-661

A large force of mostly Comanches attacked a private fort built by Silas and James Parker near the upper Navasota River. In the attack Silas and two women were killed. His daughter Cynthia Ann (9), son John (6), and three others were taken by the Comanche. In time Cynthia Ann Parker was fully adopted by the Comanche, eventually becoming a wife of Chief Peta Nocona and the mother of Chief Quanah Parker.

"Cynthia Ann Parker" by William Bridgers, 1861. Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

On March 28, 1843, a number of Indian tribes including the Caddos, Delawares, Wacos, Tawakonis, Lipan Apaches, and Tonkawas attended the first council between the Tribes and Texas officials on Tehuacana Creek just south of present-day Waco.

Minutes of Indian Council at Tehuacana Creek, March 28, 1843, Texas Indian Papers. Courtesy of Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Head chiefs for the Comanche including Buffalo Hump, Santa Anna, and others signed a treaty with John O. Meusebach, who acted on behalf of German settlers. The treaty allowed settlers to travel into Comancheria and for the Comanche to go to the white settlements. More than three million acres of land opened up to settlement as a result.

Courtesy of Texas State Library and Archives Commission, 1972/141

On December 10, 1850, representatives from the U.S. government and the southern Comanche, Lipan Apache, Caddo, Quapaw, and various Wichita bands met for treaty negotiations at the Spring Creek Council Grounds. The tribal representatives agreed to stay west of the Colorado River and north of the Llano River, to abide by U.S. laws, and to turn over fugitive enslaved people and individuals being held as prisoners. The agent for the U.S. agreed to regulate traders in American Indian territory, establish at least one trade house, and send blacksmiths and teachers to live with the tribes.

This stone is one of two placed at the meeting site near Fort Martin Scott in Fredericksburg to commemorate the signing of the treaty. However, the treaty was not ratified by the U.S. government and neither side honored its provisions.

Treaty Stone, 1850. Courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

On October 29, 1853, Alabama Chief Antone, the tribal subchiefs, and prominent citizens of Polk County presented a petition to the Texas legislature requesting land for a reservation. In part to thank the tribes for their support of the Texas Revolution in 1836, the petition was approved. The State of Texas purchased 1,110.7 acres of land for the Alabama Indian reservation. About 500 tribe members settled on this land during the winter of

1854–55. In 1855 the Texas legislature appropriated funds to purchase 640 acres for the Coushattas.

J. De Cordova's Map of the State of Texas Compiled from the records of the General Land Office of the State, New York: J. H. Cotton, 1857, Map #93984, Rees-Jones Digital Map Collection, Archives and Records Program, Texas General Land Office, Austin, TX. Courtesy Texas General Land Office

Upper and Lower Brazos Reservation was created in northern Texas. About 2,000 Caddo, Keechi, Waco, Delaware, Tonkawa, and Penateka Comanche, lived on the reservation. Five years later, attacks by white settlers and encroachments on the reservation resulted in the diverse tribes being forcibly removed to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma.

J. De Cordova's Map of the State of Texas Compiled from the records of the General Land Office of the State, New York: J. H. Cotton, 1857, Map #93984, Rees-Jones Digital Map Collection, Archives and Records Program, Texas General Land Office, Austin, TX. Courtesy Texas General Land Office

Large-scale cattle raids by Comanche became common with attacks in Cooke, Denton, Montague, Parker, and Wise counties. In December, some 300 Comanches attacked settlements in Montague and Cooke counties and escaped after driving off soldiers from the Frontier Regiment.

Saddle pad, 1870s. Courtesy Heritage Society, Houston, Gift of Mrs. Herman P. Pressler

U.S. Army Col. Kit Carson led 350 California and New Mexico volunteer cavalry against Comanche and Kiowa camps near the abandoned "Adobe Walls" trading post in the Texas Panhandle. After a battle of several hours, Carson and his troops narrowly escaped, outnumbered by about 1,400 Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache warriors.

A new technique for tanning bison hides became commercially available. In response, commercial hunters began systematically targeting bison for the first time. Once numbering in the tens of millions, the bison population plummeted. By 1878, the American Bison were all but extinct. This was a terrible blow to the American Indians whose livelihood depended on the bison and to whom the bison is a sacred animal.

Pile of buffalo hides obtained from hunting expeditions in western Kansas, April 4, 1874. Courtesy Kansas Historical Society

Kiowas and Comanche attacked a freight wagon train on the Salt Creek Prairie of Young County and killed the wagon master and seven teamsters. In response U.S. Army Gen. Sherman ordered operations to arrest any Comanche and Kiowa found away from their reservation. Chiefs Satank, Satanta, and Big Tree were arrested and put on trial. They were the first Native American leaders to be tried for raids in a U.S. Court.

Photograph 518901, "White Bear (Sa-tan-ta), a Kiowa chief; full-length, seated, holding bow and arrows"; William S. Soule Photographs of Arapaho, Cheyenna, Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Indians, 1868 - 1875; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793 - 1999; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

While on an expedition to the Llano Estacado, US Cavalry companies and Tonkawa scouts attacked a Comanche village on the North Fork of the Red River. About 13 women and children and their horse herd of some 800 animals were captured. Three soldiers were killed and seven wounded. The Comanche suffered 50 killed and seven wounded. The prisoners were sent to Fort Sill in Indian Territory.

Johnson, Chief of Tonkawa Scouts, United States Army, 1870–1875. Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Six companies of the 4th Cavalry, along with 24 Black-Seminole scouts led by Lt. John Bullis, crossed the Rio Grande and attacked a village of Lipan and Kickapoo near Remolino, Mexico. The survivors were deported to the Mescalero Reservation in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico.

A Black Seminole regiment, c. 1885. Courtesy Archives of the Big Bend, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas

By the winter of 1873‒1874, the Southern Plains Indians were in crisis. The reduction of the buffalo herds combined with increasing numbers of settlers and military patrols had put them in an unsustainable position. Led by Isa-tai and Quanah Parker, 250 warriors on June 27th attacked a small outpost of buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle. This would start the Red River (or Buffalo) War.

Red River War Kiowa Prisoners, Fort Marion, Florida, c.1875. Kiowas. Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

The Red River War officially ended in June 1875 when Quanah Parker and his band of Quahadi Comanche entered Fort Sill and surrendered. They were the last large band in Texas. The United States had now defeated the unified Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa and forcibly confined them to reservations.

Photograph 530911, "Quanah Parker, a Kwahadi Comanche chief; full-length, standing in front of tent"; Photographs of American Military Activities, ca. 1918 - ca. 1981; Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 - 1985; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

A band of Warm Springs and Mescalero Apaches under Chief Victorio terrorized southern New Mexico and West Texas. During July and August, detachments of the 10th Cavalry and 25th Infantry battled with the Apaches and denied them access to water in the trans-Pecos region of West Texas. Victorio withdrew to the mountains of Mexico, where he was killed by Mexican soldiers.

Victorio, Apache Chief. Courtesy Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Library

In 1881, a small war party of Lipan Apache attacked and looted the house of an American settler in Texas, killing two people. Thirty Black-Seminole Scouts led by Lt. John L. Bullis pursued the band of Lipan Apache raiders into Mexico. It was the last military action against American Indians conducted by the United States in Texas.

Photograph 519788, "Apache Indians as they appear ready for the warpath 1973"; Photographs of Geographical Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian from the Wheeler Survey, 1873 - 1873; Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1789 - 1999; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. Courtesy National Archive and Records Administration

In October the Tonkawa were removed from Fort Griffin, Texas, and transported by railroad to Indian Territory. Today the Tonkawa hold a yearly powwow in October that commemorates this removal and their arrival to the Ft. Oakland Reservation.

"Tonkawa or Tonquawa, – Friendly Indians – Forts Griffin & Richardson, Texas." Courtesy DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

The U.S. census counted only 470 American Indians in living Texas.

Wedding of Lindsay and Sally Poncho, the first Christian wedding of an Alabama-Coushatta Indian couple, Alabama-Coushatta Indian Reservation near Livingston, Texas. Courtesy General Photograph Collection, UTSA Libraries Special Collections 072-1723

The Snyder Act of 1924 admitted Native Americans born in the U.S. to full U.S. citizenship, extending to them the right to vote as protected by the Fifteenth Amendment. Though the Fifteenth Amendment, passed in 1870, granted all U.S. citizens the right to vote regardless of race, it wasn't until the Snyder Act that Native Americans could enjoy the rights of American Citizenship.

"Move on!" by Thomas Nast, 1871. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

In May 1967, the State of Texas officially recognized the descendants of Tigua as a tribe. The Tigua built the Ysleta Mission in El Paso in 1682. Today the Tiguas, Ysleta del sur Pueblo have a tribal government and diverse enterprises just outside El Paso that provide employment and benefits for both tribal members and regional citizens.

Ysleta Mission, one of the longest continually occupied religious buildings in the United States. Courtesy Texas Historical Commission

The Texas Indian Commission officially recognized the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas. In 1983 the Kickapoo also received Federal Recognition and received dual American citizenship with Mexico. They maintain a traditional village in Mexico that preserves their traditional ways, and their tribal headquarters is in Eagle Pass, Texas.

Southern Kickapoo people building a winter house in Nacimiento, Coahuila, Mexico, 2008. Courtesy Fernando Rosales

The 2000 census counted 118,362 people in Texas who identified themselves as exclusively American Indian.

Courtesy Bullock Texas State History Museum

On March 18, 2009, the State of Texas legislature passed resolution HR 812 recognizing the Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas.

Bill HR812, 2009. Courtesy Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas

On April 25, 2013, the Texas State Legislature passed House Bill 174, which named the last Friday in September as American Indian Heritage Day in Texas. It recognizes the historic, cultural, and social contributions American Indian communities and leaders have made to the state.

Courtesy Bullock Texas State History Museum

From People Across Texas

More Texas History Stories or go back to the Bullock Terrazzo

- American Indians BCE- 1600

- African Americans 1821-1865

- Buffalo Soldiers 1850-1880

- Cattle Ranchers 1850-1880s

- Conquistadors 16th Century

- Frontier Folk 1820-1850

- Missionaries 1500-1750

- Roughnecks 1890-1950

- Texas Rangers 1821-Present

- Vaqueros 1519-present

- Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) World War II